RITESH MESHRAM

in the womb of the land | solo | chemould prescott road | 2018

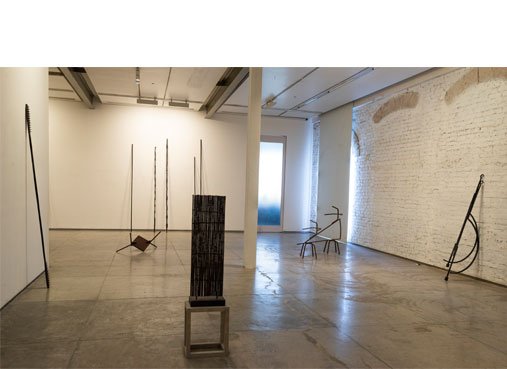

Ritesh Meshram’s recent sculptures could be called Unfound Objects. They give the impression of familiarity, a few seemingly made of articles one could purchase in a hardware store, others of components recovered from a scrap heap. Yet, the forms sprang entirely from the artist’s mind, and were created by hammering, cutting, casting and soldering metal to his precise specifications. They are carefully designed artefacts that echo or mimic bricolages.

Mild steel, which predominates in the sculptures, appears a natural choice of material for Meshram, who was born and brought up in a steel worker’s family in Bhilai, site of a massive public sector manufacturing plant established in 1955. However, the connection could be coincidental, since he took to steel after years of practice as a painter, and a previous switch to sculptures made from objets trouvés.

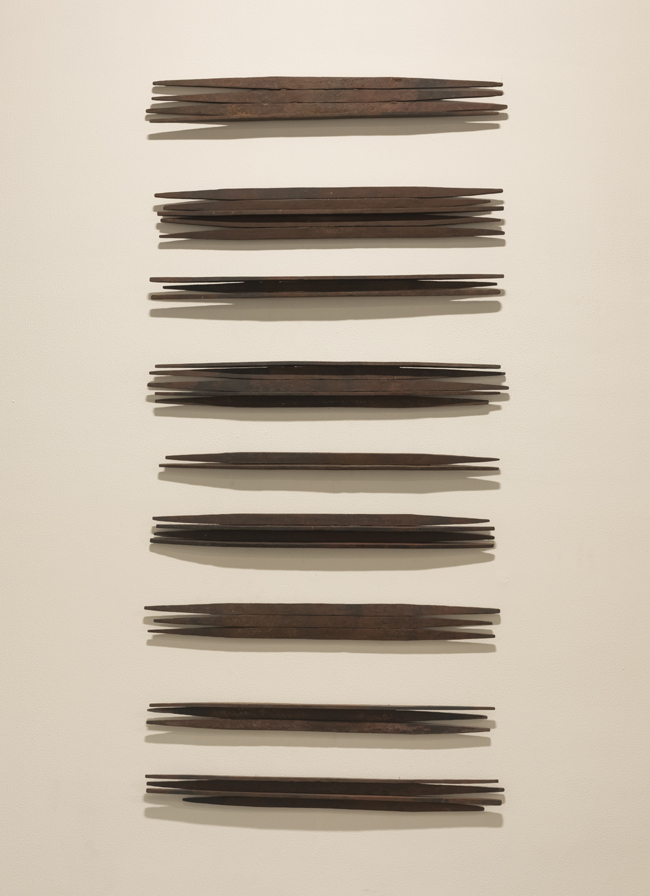

Through these shifts, his art has retained certain persistent features, displaying a quirky sense of humour and often hovering tantalisingly between formalism and conceptualism. In the present body of work his formalism is best illustrated by the treatment of metal. He has left some surfaces raw or applied a patina to enhance their shabby chic. In other instances, he has brushed on a thin coat of black or employed a spray finish to ensure the preservation of each minute detail.

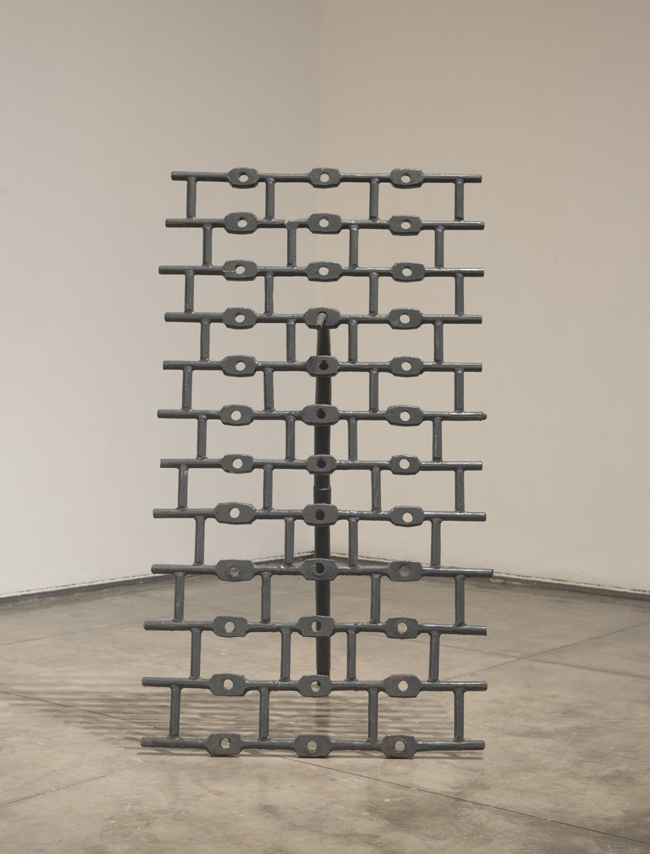

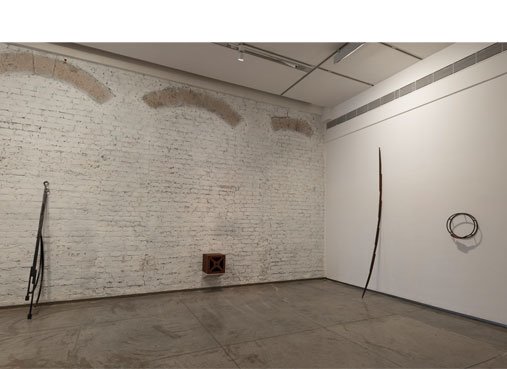

Conversely, he has also used silver and thick grey enamel paint, commonly found on safety grills in Indian apartments, to invoke the aesthetic of middle-class homes, and thereby bring social questions into the act of interpretation. While the bulk of the sculptures are untitled, he calls the one painted grey, Window to Watch, underscoring its political intent. Similarly, the title of Piece of Land nudges us to take a closer look at what appears at first sight an inebriated table struggling to right itself. In other cases, as with a ladder that has rungs only near the top, the very structure invites metaphorical readings, needing no textual prompt.

A group of toys, simple yet deceptive, embody the artist’s whimsy and impishness. A wheel cannot turn, a cart is overloaded, each object’s apparent function is undercut. In their scale and form, these objects recall an immense tradition of toy-making stretching back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, which bequeathed us no monumental icons, but a plethora of figurines and playthings. Meshram has also produced a set of meditative sculptures as material correlatives of intangible notions, for example the idea of something hidden and unreachable. In these, as with the toys and sculptures that resemble spears and ladders, he harnesses the power of archetype alongside the open-endedness and polyvalence characteristic of contemporary art.

Girish Shahane

gallery display

Metal echoes strength.

The first impression when you view a piece of metal is that of strength; It’s characteristics, its resonance, it’s internal density and dexterity gives us an indication of its potency.

Metal is sound; Metal resonates; it is an expression of strength. Concurrently, it is also an expression of suppression. Despite its density, it’s malleability, allows us to exploit, to manipulate as one desires. The metaphor that then captivates me, is evaluating miners, who unearth iron ore from mines, transport it, melt it, and fragment it from its raw form – that of iron ore. For me, the journey or the miner and the metal draw parallels.

In conjunction with this allegory, my works are both raw and formed. Owing to their character, I have oxidized some pieces so that they give us a sense of age; others have been painted silver or black and for others I have left them to rust. With rusting you see the impression of the hammer, with black you see the strength of the hammer, whereas with silver the hammer leaves behind it’s textures – bringing out a completely different feeling of the metal.

What I have also explored through my metal work is to draw a similarity in the tools of the labourers that helped me make this work. There is such an aesthetic in these tools – whether it is the design, the sound they make, or their form. For me to create a new aesthetic with the already existing forms was something that inspired the process of my own work.

Ritesh Meshram